Permanent Revolution: Myth, Reality, and Relevance

By Sami El-Sayed

Permanent Revolution is perhaps one of the most controversial theories in modern history.

It had its most visible practical relevance in the early 20th century when it was advanced by Leon Trotsky in the context of the tasks of the Russian Revolution. Trotsky had posited that, given the weakness of the Russian bourgeoisie, the Russian working class needed to take on a leading role in the struggle for democracy. But because of the weak nature of the Russian capitalist class, the working class would necessarily have to go past the constraints of capitalism and carry out a socialist transformation of society. Rather than the stageist view, which argued that “backwards” (i.e. underdeveloped or pre-capitalist) societies needed to go through a stage of bourgeois-democratic, capitalist development, in order for a socialist revolution to be possible, Permanent Revolution maintained that socialist revolution was not only possible but in many senses imminently necessary.

So, where’s the controversy? Due in part to the destruction of the Russian working class during the Civil War, the Bolshevik grip on power was extremely vulnerable and insecure. Since 1917, the Bolsheviks had adopted a perspective that ‘world revolution’ was on the cards and that Russia was simply one of many dominoes to fall to the rising tide of communism. Soon, Germany and other states would turn red, and they would be able to link up and make safe the gains of the Russian Revolution. By 1924, the Bolsheviks were appropriately disappointed when the German communist movement proved incapable of the task of successfully carrying out a revolution of its own. And then Lenin died. World revolution did not look like it was immediately on the cards anymore.

Article originally published in Issue 6 of Rupture, Ireland’s eco-socialist quarterly, buy the print issue:

As often happens to movements in a difficult situation with no idea what to do, and without a major leadership figure holding everyone together, the Russian communist movement split.

On one side, Trotsky and many of his supporters held to the previous position, that the Russian Revolution could not survive in isolation and revolution in Western Europe was required in order to safeguard it. On the other side of the argument, Stalin argued that it was time to consolidate and attempt to build socialism in Russia, developing the theory of ‘Socialism In One Country’.

‘Socialism In One Country’ was a bit of a fresh coat on stageist theory, which is why it is so counterposed to Permanent Revolution. Rather than insisting that there are stages of development which society must go through in advance of a socialist revolution, Socialism in One Country basically inverted the theory; after the socialist revolution, the Soviet Union had to go through stages of industrial development before achieving communism, and that rather than holding out for revolution in Western Europe and linking up with advanced industrial societies there, the world communist movement now had to turn to the defence of the Soviet Union while it carried out its own, condensed, form of industrial development that capitalism should have carried out, had the stageist schema been accurate. This would then go towards correcting the imbalance of class power between the Soviet working class and peasantry. This strategic turn required effectively selling out every revolutionary movement on the planet, if it meant further solidifying the USSR on the world stage with erstwhile allies in the “progressive” capitalist states (the brutal colonial powers of Britain and France in particular). Rather than forces of revolution, communist parties became wings of Soviet foreign policy designed to influence the ruling class towards a less anti-Soviet stance.

““Rather than forces of revolution, communist parties became wings of Soviet foreign policy.””

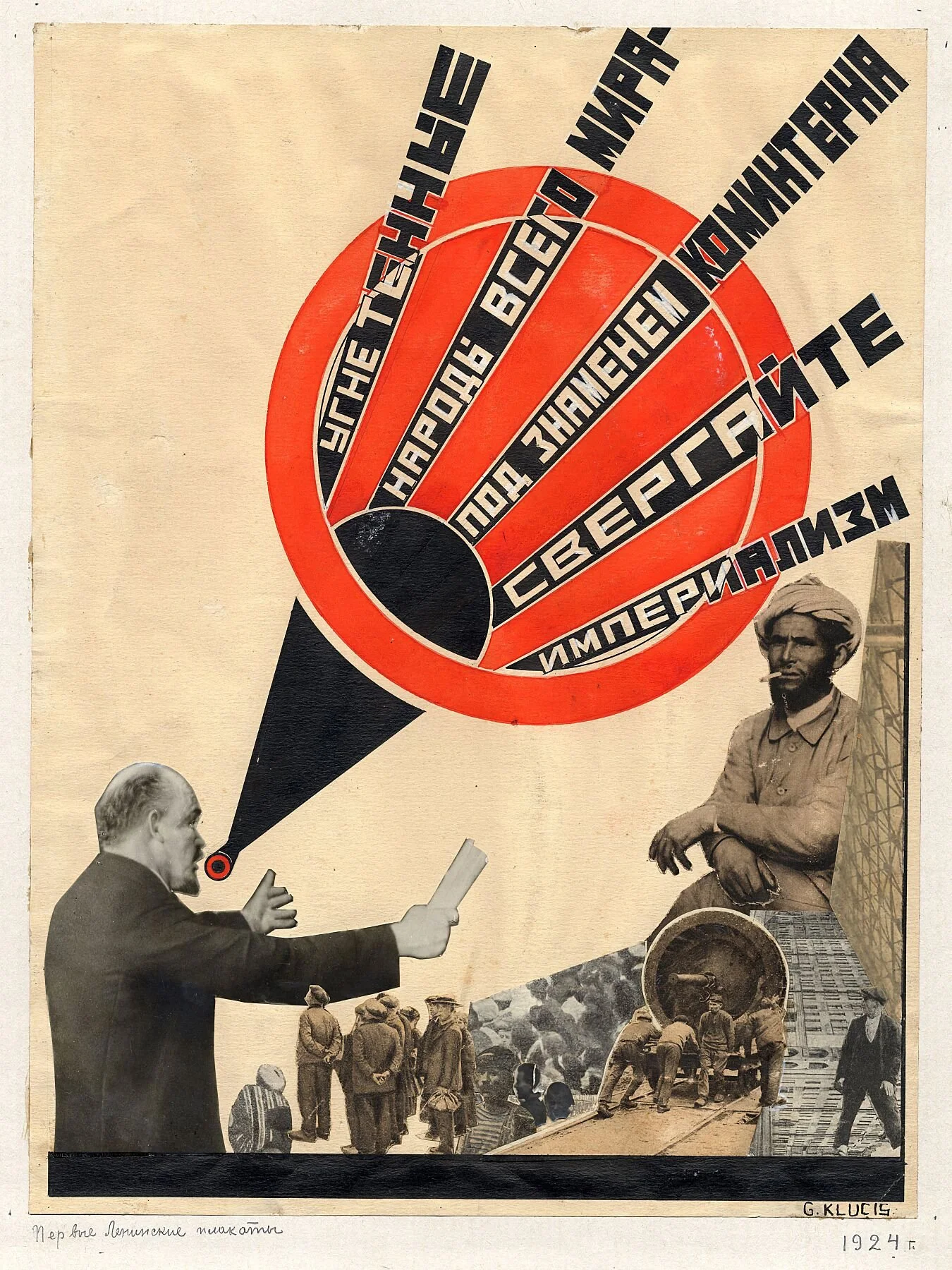

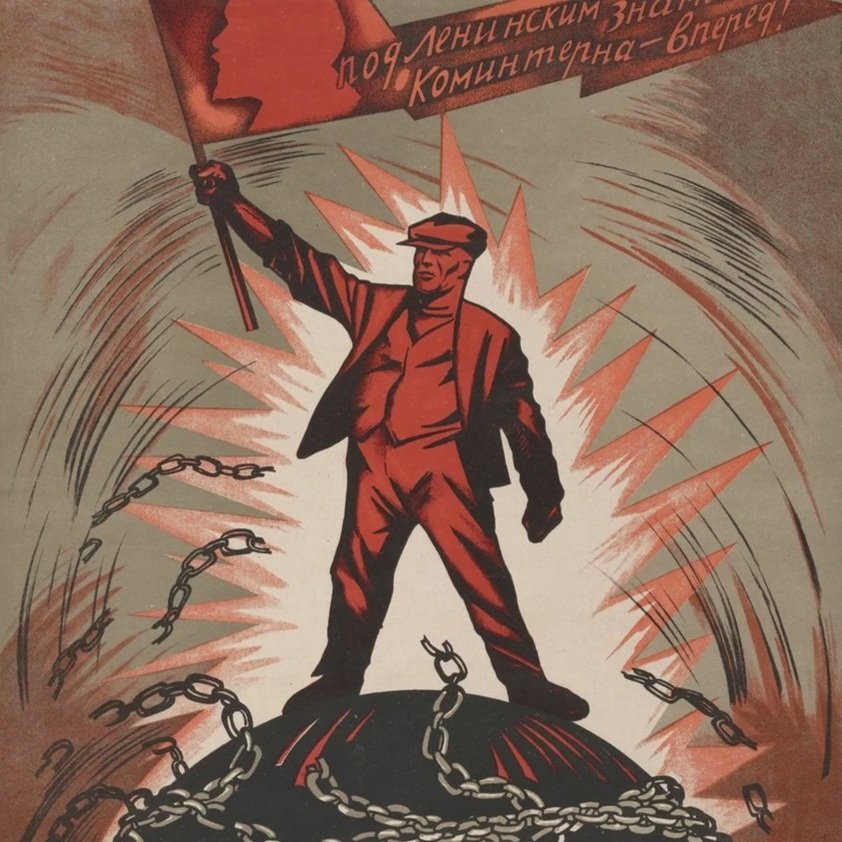

Using their hold over the party-state apparatus, the centre faction of the Communist Party under Stalin systematically repressed Trotsky and other oppositionists, ultimately executing all those who did not flee into exile. An essential part of the Stalin faction’s rise to power was the dissemination of propaganda discrediting his opponents, and considering the centrality of Permanent Revolution for what would go on to become the Trotskyist movement, great effort was put into attacking the theory. That it remains controversial a century later is a lasting testament to Stalin’s extremely successful career as a counter-revolutionary dictator.

We need to go deeper

But the story doesn’t start here. Permanent Revolution was a theory central to the Russian Revolution - but it is not a theory developed from the ground-up by Trotsky, and in fact can trace its development back to Marx and Engels, but mostly to the Marxist thinkers of the Second International. Similarly, Stalin was a hugely repressive tyrant, but most of the intellectual legwork around Socialism In One Country was in fact done by Nikolai Bukharin (who Stalin later stitched up and executed in 1938).

So, what exactly is Permanent Revolution? In its most developed form, as put forward by Leon Trotsky, it is both a descriptive and prescriptive theory of revolution. To make it clear in concise terms, we will summarise it (as much as it can be summarised) and then proceed to the historical background:

The bourgeoisie in underdeveloped countries will often be incapable of playing a progressive role. For example, the Russian bourgeoisie was incapable of playing a progressive role because it was both numerically weak, and its economic and social interests were completely tied up in the existing Tsarist system due to the fact that the Russian bourgeoisie were thoroughly tied to the landlordism which kept the peasantry oppressed. This meant that a key task of every bourgeois-democratic revolution, land reform, was beyond their scope of action, and they were consequently unable to mobilise the peasantry behind them (other key tasks can be understood to be national independence/unity, abolishing monarchy etc - outcomes which lay the social basis for capitalist development). On top of this, the imperialist influence on the Russian economy from foreign capital limited the Russian bourgeoisie’s scope for economic development and industrialisation in particular, therefore limiting the degree to which the Russian capitalist class could become independent from landlordism in general. As such, the Russian bourgeoisie was incapable of being progressive, so long as it adhered to its own material interests.

This process historically happened in ‘backwards’ or underdeveloped nations, and today persists in the context of the imperialist domination of nations. It follows directly that for many of the same reasons, nations developing late into capitalism were incapable of following the model of British, French or German capitalism. The bourgeoisie of these developed nations had already taken on an international dimension, the very pursuit of capital accumulation itself relied on the pillaging of other nations and of nature. Consequently, the development of capitalism elsewhere in the world, both in the form of technological advancements and their own pursuit of market share and capital accumulation in new and developing markets, was distorted and hindered, allowing those who got there first even greater power to loot the world further. ‘Latecomers’ are and always have been structurally locked into a subordinate position in world capitalism from the get-go.

““‘Latecomers’ are and always have been structurally locked into a subordinate position in world capitalism from the get-go.””

As such, in order for the working class to fight for its own material interests, it takes on a leading role in the struggle for bourgeois-democratic rights. In doing so, in order to break the fetters on national development, the working class will find it necessary to go further than bourgeois-democratic tasks. As such, the bourgeois-democratic revolution will transform into a revolutionary socialist struggle by necessity. And therefore a socialist revolution can occur first in a peripheral state rather than the most developed ones. However there is a problem with this perspective: in ‘backwards’ nations, the weakness of the working class and lack of industrial development, as well as encirclement by imperialist powers, meant that underdeveloped nations (eg. Russia) are unable to develop socialism alone. However, on a world scale there is a sufficient economic base for socialism. Therefore, the ultimate survival of a successful revolution in the underdeveloped world necessitates revolution in more ‘advanced’ nations.

There is a lot that goes into this, in particular there are assumptions about the role of the bourgeoisie and its relationship to imperialism, as well the question under the surface of how capitalism develops on a global scale i.e. is it a ‘world system’ or a ‘global mode of production’? This is fully tied up with Trotsky’s original contribution to the theory of Permanent Revolution in the theory of Uneven and Combined Development. Such questions and the Marxist theoretical divergences around them warrant their own extensive articles.

However, to lay a foundation for addressing these questions in the future, we have to go back to the revolutionary struggles of 1848, when the Communist Manifesto was first published, and go from there. In that period, the working class was a tiny minority within the general population, and revolutionary movements were numerically dominated by the peasantry and middle classes, not the proletariat. Rather than ignoring this reality, Marx had argued against sectarianism within the communist movement holding that communists should involve themselves in liberal organisations as the most enthusiastic and radical proponents of democracy. The Communist Manifesto outlines Marx’s perspective well:

“The Communists turn their attention chiefly to Germany because that country is on the eve of a bourgeois revolution that is bound to be carried out under more advanced conditions of European civilization, and with a much more developed proletariat than that of England was in the seventeenth and of France in the eighteenth century, and because the bourgeois revolution in Germany can be but the prelude to an immediately following proletarian revolution.”[1][2]

However, his experience and observations of the failed revolutionary struggles of both France and Germany in that period led him to the conclusion that the capitalist class was completely unwilling to carry out a bourgeois-democratic revolutionary struggle.

The betrayal by the liberals of the movement for democracy led Marx and Engels to the conclusion that in order for the struggle for democracy to be successful it must be led by the working class first and foremost. This is the starting point of Permanent Revolution and one of the key foundational organisational principles of Marxism more generally which posits the necessity of independent political organisations of the working class. This principle, which was fought for and defended within the Social Democratic movement in the early 1900s, did not just fall out of the sky; it is one of the concluding prescriptions of Marx’s own developing theory of permanent revolution, a theory which became increasingly dominant in the thinking of Marx and Engels in the second half of the 19th century.

Having established that the starting point of Permanent Revolution is the inability or unwillingness of the bourgeoisie to play a progressive role, we have to ask ourselves: Why? Why was the capitalist class unable to play a progressive role? For Marx, the bourgeoisie were simply more fearful of the empowered masses than they were of continued dictatorship and subordination either to Bonapartism or absolute monarchy. However, in the intervening years between Marx and today, capitalism itself developed and so did Marxist theory.

Social Democracy & Permanent Revolution

Contrary to the Leninist mythos, the Social Democratic movement of the early 20th century was not entirely dominated by a ‘mechanical’ approach to historical materialism. Seeing history through the prism of firm stages (i.e. stageism), with society needing to advance through each stage - first feudalism, then the bourgeois revolution, then capitalist development, then the socialist revolution - was common but by no means universal within Social Democracy, and there was a powerful left wing which consistently challenged it. The great thinkers of Marxism, particularly the likes of Kautsky, Parvus, and David Ryazanov (who was executed by Stalin as a ‘Trotskyist’ in 1938 and subsequently written out of history) were more than a little critical of the de facto stagist approach advanced by Lenin’s mentor, Plekhanov. Writing in 1902, Kautsky argued,

“Western Europe is becoming the bulwark of reaction and absolutism within Russia. The rotten throne of the tsars is falling apart and might have collapsed long ago had the West-European bourgeoisie not continuously reinforced it with its millions ... The Russian revolutionaries might have dealt with the tsar long ago if they had not been compelled to wage a simultaneous struggle against his ally – European capital.”[3]

The dynamics described by Kautsky here are the dynamics of imperialism. The penetration of European capital into Russia transformed the social, political and economic development of the Russian Empire. There was now a developing Russian capitalism, with a bourgeoisie that was both economically weak and socially invested in Tsarism, as discussed earlier.

This clearly did not match the schema set out by the more mechanical Marxists, which posited that society developed through set stages. Instead, Russia went through what Trotsky would go on to describe as ‘uneven and combined development’. This resulted in the deployment of advanced capitalist production techniques in a country which had an almost entirely peasant population and agrarian economy, and socially and politically was still effectively feudal in nature. The penetration of imperialist capital into Russia, combined with state-directed investment, soon transformed the dominant mode of production into capitalism.

Capitalism, rather than being won ‘from below’ by a developing Russian bourgeoisie through a revolutionary struggle in which it led all classes in society, was imposed ‘from above’ by world imperialism and a monarchy adapting itself to survive in the new world economic system. The uneven nature of global capitalist economic development combined with the backwards social and political institutions of Russia, resulting in a society that had both a backwards feudal ruling class and some of the largest centres of industry on the planet with a correspondingly militant industrial proletariat. What this meant was that while capitalism was economically developing in Russia, none of the political or social tasks (parliamentary democracy, land reform etc) of the bourgeois revolution had been carried out, nor was there a Russian bourgeoisie with the strength to do so. Kautsky again made much the same observation about imperialism’s decisive influence over the trajectory of Russian political development after its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War:

“The revolution in permanence in Russia cannot fail to have repercussions on the rest of the European continent … state bankruptcy and the loss of many billions that European capital has lent to Russian absolutism … But it is not necessary for the dictatorship of the proletariat to come about in order to declare state bankruptcy … It is quite likely that the European capitalists will be punished together with their fellow sinners. Had they exerted their influence in a timely manner to compel the tsar to introduce a liberal régime, they could perhaps have prevented the revolution and saved their coupons. Through their unconditional support for the infamies and stupidities of the absolutist system they have fortunately prevented the establishment of the only governmental system that might have avoided state bankruptcy – a liberal government.”[4]

He also referenced Japan, which to us acts as a more positive (though not necessarily “good”) example of the dynamics of uneven and combined development:

“It is clear that the Japanese victory must have the greatest influence on Japan itself. Here, we can deal with that subject briefly because the war will not change the direction and nature of its development but only accelerate its tempo ... In general, though, it can be said that the country will develop the capitalist mode of production in its own peculiar way even more than before. The distinguishing mark of Japan, and the root of its power, is that the country was able to leap over an important stage of development: the decadence of feudalism.”[5]

Far from the mainstream Trotskyist caricature of Social Democracy as mechanically stagist, Kautsky’s argument was just one such example of the flexible thinking of Marxists in that period, and it is no surprise that such thinking would be a major influence on Trotsky’s own, more developed, theorisation of Permanent Revolution.

““The Social Democratic movement of the early 20th century was not entirely dominated by a ‘mechanical’ approach to historical materialism.””

Kautsky was far from alone in this regard, particularly in the context of Russian Marxism. The split forced by Lenin and the Bolsheviks at the 1903 conference of the Russian Social Democratic and Labour Party also headed off what was the beginning of a debate on Permanent Revolution, instigated by Ryazanov who authored a dissenting document to Lenin and Plekhanov’s proposed party programme. Hitting almost the exact same beats as Trotsky would three years later in Results and Prospects, Ryazanov stressed the unique conditions of development in Russia: namely the disproportionately advanced development of the industrial working class relative to the bourgeoisie, and the ‘political sterility’ of the Russian bourgeoisie. Using the example of the German Revolution, Ryazanov argued that Marx and Engels had made an error in overestimating the progressive role of the German bourgeoisie, and were subsequently caught unawares:

“[If] we want to avoid repeating that mistake, if we want to avoid making our own strictly ‘subjective’ mistake, then we must not close our eyes to one of Russia’s ‘special’ characteristics, namely, the fact that our bourgeoisie has shown itself to be emphatically incapable of taking any revolutionary initiative whatever.”[6]

This is Permanent Revolution in its essence. And there was nothing strange or ‘Trotskyist’ about the stance; it was mainstream enough that James Connolly reproduced an essentially identical analysis of the dynamics of Irish revolutionary struggles in his magnum opus, Labour in Irish History, first published in 1910. Connolly, like most Social Democrats, was a Permanent Revolutionist.[7. ‘The Cause of Ireland is the Cause of Labour’ was a pithy summary of an analysis that the national bourgeoisie cannot be relied upon and that the working class would have to lead the struggle against imperialism.

Between then & now

Between Marx and Trotsky, Permanent Revolution developed in leaps and bounds, as outlined in the previous sections. But what about between Trotsky and today? It has been a full century since the factional battles in the world communist movement unfolded around Permanent Revolution: How have things panned out?

““The states that were underdeveloped a century ago are still underdeveloped now.””

In layman’s terms, Permanent Revolution outlines that there is no way for underdeveloped states to follow the same road to economic development that the core capitalist states (broadly encompassed by ‘The West’, or ‘Global North’) have. There can be no more Germanys or Britains emerging into the world like they did in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the last century that has proven broadly true. The states that were underdeveloped a century ago are still underdeveloped now; it is beyond doubt that the nations of Latin America, Africa, and Asia do not enjoy the same level of wealth and living standards as those in Europe and North America, and there is plenty of empirical evidence that rather than the gap closing between the core and the periphery, it is getting larger and larger.[8] That does not mean there is nothing more to add to this.

The fact is that whether in Latin America or Africa, states which had liberated themselves from direct colonial domination were forced by the global capitalist system to maintain more or less similar economic relationships with their former colonial overlords in order to survive, not in the least because of force arms, coups d’état, electoral interference, and so on.[9] This spawned its own school of economic and social decolonial thought in Dependency Theory, heavily influenced by Trotsky’s theory of Uneven and Combined Development.[10] Regardless of the varying economic methods attempted by the decolonised nations, such as Import-Substitution Industrialisation or heavy state-led investment, they were constrained by operating within the global capitalist system and were never able to achieve a fully autonomous road to capitalist development.

There are a number of key exceptions to this rule, mostly in Asia. The development of Taiwan and South Korea into countries with a ‘first world’ status, that is, states with high advanced economies on the level of those in the Global North, would superficially indicate that some alternative road to capitalist development with strong domestic industry was feasible. However, it is impossible to ignore that both these countries only achieved the level of development they currently have on the back of massive subsidies from the United States in particular as part of their global anti-communist effort. In the case of Taiwan, over 40% of its domestic capital formation in the 1950s was funded on the back of grants (not loans) from the United States.[11] Similar patterns are seen elsewhere.

China and Russia also act as interesting case studies, in that both countries are clearly at a stage of economic development higher than that of most states in the periphery, and it is no coincidence that both these states were at one stage operating on a Stalinist model of economic development: the expropriation of the bourgeoisie, a (bureaucratically) planned economy and effectively ending the rule of markets. China in particular used the Stalinist model to leverage its huge population and natural resources, before enacting capitalist market reforms and becoming an emerging world economic capitalist superpower, even while most of its population does not enjoy living standards to match. The Soviet Union’s ability to chart an alternative course of economic development was a huge source of influence in the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutionary struggles around the world, with perhaps the most successful iteration in Cuba, with its revolutionary process allowing it to achieve better results in numerous fields (such as healthcare and child mortality) than its vastly more wealthy neighbour, the United States.

Marxist thinkers have attempted to grapple with cases like Cuba since before even the Cuban Revolution happened, with numerous contending theories emerging to explain the processes at play, usually focusing on the prior existence of the Soviet Union as an explanation. Tony Cliff’s theory of Deflected Permanent Revolution and Ted Grant’s of Proletarian Bonapartism are interesting and useful to study, but it seems hard to believe that they are the last word on this issue, and both have their own problems.[12]

More examination needed

Permanent Revolution is a theory with a rich history that has, in most of its basic claims, held up. That does not mean that there are no questions to answer. The anti-colonial revolutionary period provides a vast wealth of experience and evidence which needs to be drawn on, and future developments of the theory must rest on a reassessment of the nature of imperialism in the context of 21st century capitalism. The nature of capitalism today is dramatically different to that of the mid-late 20th century, which means that how various social forces interact both with each other and capitalism has significantly changed. Permanent Revolution is long overdue another examination.

Notes

Marx, K. and Engels, F (1848) The Communist Manifesto Ch. 4, ‘Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties’.

For more information, providing excellent and detailed documentation of the development of the theory of Permanent Revolution, see Day, R.B. and Gaido, D. (2009) Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record, Historical Materialism Book Series Vol. 21.

Kautsky, K. (1902) ‘The Slavs and Revolution’, Iskra No. 18.

Kautsky, K. (1905) ‘The Consequences of the Japanese Victory and Social Democracy’, Die Neue Zeit 23(2).

Ibid.

Ryazanov, D. (1903) ‘The Draft Programme of ‘Iskra’ and the Tasks of Russian Social Democrats’

See Labour in Irish History for Connolly’s thoughts on the matter.

Conway D. and Heynen N. (2008) ‘Dependency theories: From ECLA to André Gunder Frank and beyond’. In Companion to Development Studies, (Desai V., Potter R., eds), Routledge, pp. 92-96.

Bates R.H., Coatsworth J.H., Williamson J.G. (2006) ‘Lost Decades: Lessons from Post-Independence Latin America for Today’s Africa’, National Bureau of Economic Research No. 12610.

Lopes T.C. and Júnior M.C.d.P.G. (2013) ‘Trotsky’s Law of Uneven and Combined Development in Marini’s Dialectics of Development’, Political Economy, Activism and Alternative Economic Strategies: Fourth Annual Conference in Political Economy. The Hague, 9-11 July.

Castle-Miller M. (2013) ‘Qualifying Dependency Theory in Light of the Republic of China (Taiwan)’

For an outline on both theories, in the words of their authors, see Cliff, T. (1963) ‘Deflected Permanent Revolution’, International Socialism No. 12 ; Grant, T. (1949) ‘Reply to David James’, Internal Bulletin of the Revolutionary Communist Party ; Grant, T. (1978) ‘The Colonial Revolution and the Deformed Workers' States’, Militant International Review.