Eyewitness in Brazil: PSOL Heatedly Debates Its Relationship to Lula

Should Socialists Ally with Lula or Prepare to Oppose His Government?

By Cian Prendiville

Twelve months ago, the left across the globe breathed a collective sigh of relief as we heard the far-right president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, had been beaten by the centre-left former president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. One year later, the tensions and struggles in the Brazilian socialist party PSOL are a cause of concern for us all, argues Cian Prendiville, an international observer at PSOL’s recent convention.

I was honoured to attend the 8th National Congress of Brazil’s broad socialist party, PSOL (Partido Socialismo e Liberdade - “Socialism and Liberty Party”), from September 29 to October 1. Almost 450 delegates came together, representing 53,000 activists who participated in local and regional conventions. They were joined by many more national and international observers keen to follow the debates. The traumas of the last decade weighed heavily over the convention, as we gathered in the same city that only months beforehand had been the site of the Bolsonarist “insurrection.” At night, we hung out and discussed politics in the very petrol station, bar, and restaurant from which came the name “Operation Car Wash” - a major investigation in the name of “anti-corruption” that led, among other things, to Lula’s imprisonment in 2018, blocking his attempt to run in the 2018 elections.

That “operation” saw Lula spending almost two years in jail on allegations of corruption before the Supreme Court annulled all charges and ruled the imprisonment unlawful, allowing Lula to run once more. However, the election was very closely fought. A swing of 0.9 percent from Lula to Bolsonaro would have seen the outcome reversed. The far right did not accept the election results, with thousands of Bolsonaro supporters storming the National Congress, Supreme Court, and Presidential Palace, and calling on the military to stage a coup.

Bolsonaro’s four years as president were disastrous for workers, indigenous people, women, LGBT+ people, and the planet. His COVID-denialism saw 700,000 people die as he put the profits of big business before protecting and supporting people. Deforestation of the Amazon increased dramatically, with 10,800 square kilometres being chopped down in 2020 alone. He attempted to atomize workers and cripple their unions, outlawing the collection of union fees at payroll level, and pushing deregulation and casualization of work.

The spectre of Bolsonarismo still haunts the country, with the right having a majority in Brazil’s National Congress and controlling many key states and cities. Just days after the PSOL convention, public transit workers and water workers in São Paulo went out on strike against the privatisation plans of the right-wing governor. Lurking in the shadows is Bolsonaro himself, plotting another run for president in 2026.

PSOL Navigating Rough Waters

These are the rough waters that the broad socialist party PSOL is trying to navigate. It is a significant force, with almost 300,000 members, 13 deputies in the National Congress of Brazil, and over 100 representatives in state assemblies and city councils. It was formed in 2004 as a split from the PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores - “Workers’ Party,” the centre-left party Lula represents), speaking out against neoliberal attacks on pensions by the Lula government of the time. The party’s membership has multiplied significantly since then, with more splits from the PT and splits from a revolutionary left party PSTU joining, as well as the 2018 merger into PSOL of Revolução Solidária (“Solidarity Revolution”) which leads the important housing movement, MTST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Teto - “Homeless Workers’ Movement”).

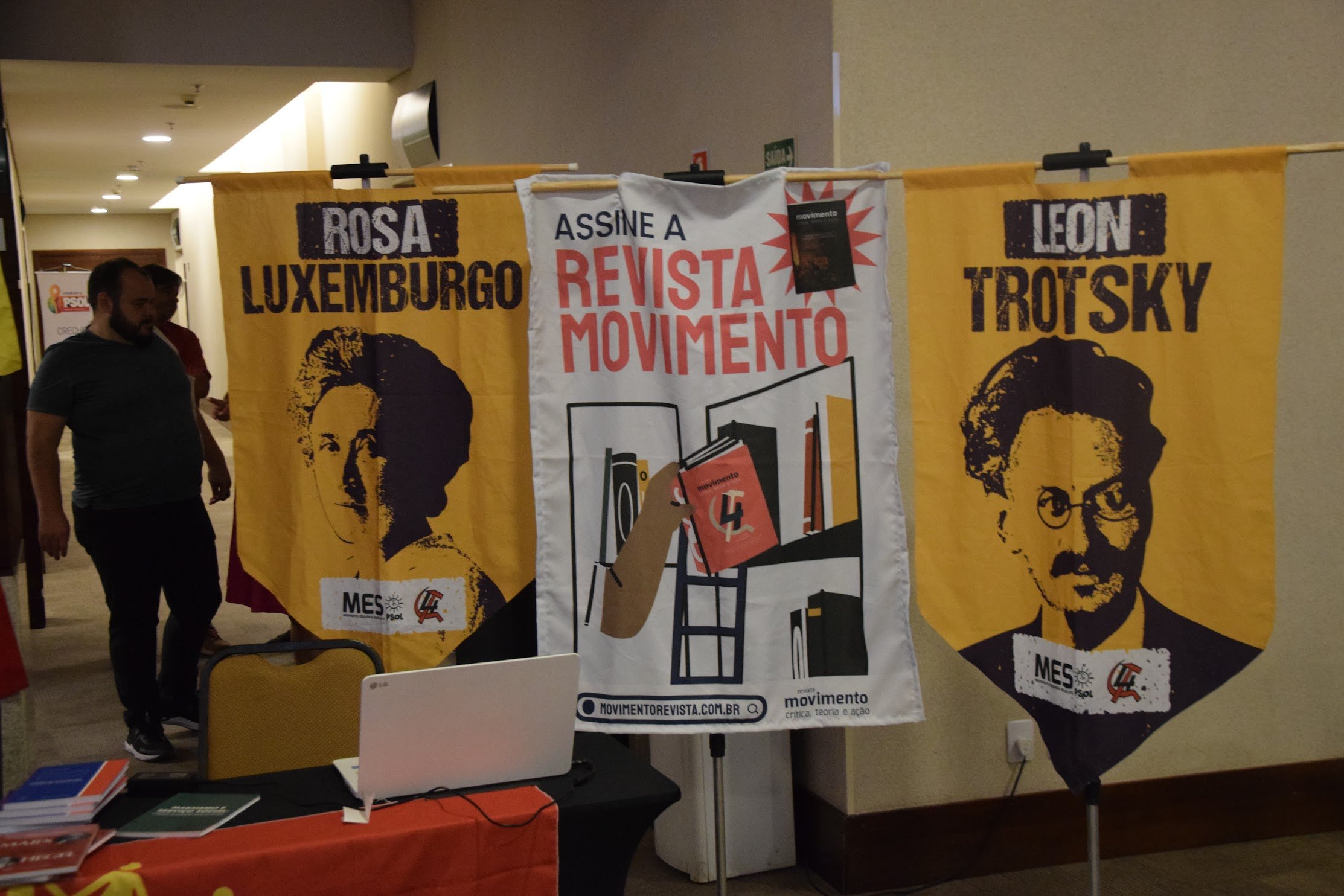

A stall at the congress

In last year’s elections PSOL backed Lula, but after a serious debate they agreed not to join his government, pointing in particular to the inclusion of many neoliberal and right-wing politicians as ministers in the coalition. However, it is not as black and white as being part of the coalition or not, with individual PSOL members being invited to play important roles in government. The most significant of these was the agreement that indigenous activist and PSOL member Sônia Guajajara would accept the invitation from Lula to be a minister in his government and to form a new Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. This was seen as a historic attempt to undo some of the centuries of oppression they have faced.

It was against this backdrop that PSOL held its 8th National Congress from September 29 to October 1. (Note: the term “convention” is often used rather than “congress” in this article to refer to the national meeting of PSOL delegates, in order to avoid confusion with Brazil’s legislature, which is also called the National Congress).

A Divided Convention

At the convention, two main blocs became clear. Por um PSOL de Todos as Lutas (PTL - “For a PSOL of All Struggles”) were a clear majority from the outset, with the Bloco de Esquerda (“Left Bloc”) a militant minority. Within each bloc were numerous different groupings and a veritable alphabet soup of acronyms to learn (see graph).

According to the PTL majority, the party is divided between those who understand the threat from the far right and those who don't. They argue the Left Bloc has been slow to realise how serious the threat of fascism is, and that they risk aiding the far right by focusing on opposing the Lula government. PTL is led by PSOL Popular, an alliance of two big organisations: Primavera Socialista, who have been part of the leadership of the party since its founding, and the newer Revolução Solidária (RS) mentioned above. RS is closely aligned with Guilherme Boulos, who is considered by some a possible future “heir” to Lula, winning his endorsement in the run for mayor of Brazil’s largest city, São Paulo, next year.

The left wing of PTL, Semente, succeeded in pushing for PSOL not to join Lula’s government, and have called for criticising the PT when needed. However, along with their allies in PTL, they see Lula as a uniquely popular figure able to challenge Bolsonarismo, and they emphasise the importance of united fronts with the PT and Lula. While there are debates within PTL on the precise balance of collaboration and criticism, they are united in seeing representatives like Boulos as key to winning support from PT to PSOL.

For the Left Bloc, the core issue is the need for independence from the Lula government and to appeal to those workers and poor people who are not Bolsonarists but are sceptical of the PT. They believe more and more people are likely to grow frustrated with Lula and his coalition with right-wing individuals and parties, as they manage a capitalist system in crisis. While supporting united front work and alliances with PT, they emphasise the need for independent socialist messaging in that. They criticise PSOL’s current leadership for not doing this and instead blurring the lines with PT. In particular, the Left Bloc warned of a slow drift into joining the Lula government.

Within the Left Bloc, a minority argued the first error by PSOL was the decision not to suspend Sônia Guajajara from the rights and responsibilities of PSOL membership while serving as a minister. But the largest group, MES (Movimento Esquerda Socialista - “Socialist Left Movement”), defends that decision given the exceptional significance of having a Ministry for Indigenous Peoples. They argue, however, that this should be the only exception and that PSOL must more consistently oppose measures from Lula, such as the recent tax changes MES led the left opposition to.

Lula’s First Budget and Tax Reforms

The recent tax reforms were one of the first issues where PSOL deputies in the National Congress were split, with those supporting the PTL majority voting in favour while those aligned with the Left Bloc voted against. This debate featured a little at the convention, with the Left Bloc arguing the changes were not progressive, and there was no need to support them, while PTL argued there was nothing particularly worth opposing.

There was also a clash over the first budget from Lula, which PSOL as a whole publicly opposed. In the debates, some PTL speakers explained they had opposed the budget because there was no time to improve or amend it while the Left Bloc opposed the budget outright and accused some of initially wanting the party to support it.

Speakers from PSOL Popular accused the Left Bloc of being “abstract revolutionaries” who criticised things from the sidelines so they could sleep with a clean conscience rather than actually engaging in the difficult compromises and alliances needed to get more funding for key projects, alleviating some of the poverty people face, and building the base of support for PSOL.

Election Strategy for 2024

One of the concrete issues under debate at convention was the strategies and alliances that could be built in the local and state elections in 2024.

The PTL emphasised the primary aim in these elections as being to stop the far right, arguing for a focus on building alliances with left and centre-left parties as a key means of doing that. Their resolution said that any coalition with parties that have supported Bolsonaro or defended neoliberalism were generally prohibited but allowed for exceptions to that rule with agreement of the National Directorate.

The Left Bloc opposed this possibility of local alliances with right-wing parties but supported the idea of alliances with left and centre-left parties, emphasising that PSOL should also put forward radical demands of its own even when in such alliances.

Interestingly, in this debate Resistência (the largest group within Semente) did not support the PTL resolution, opposing the idea of alliances with right-wing parties. However, they also explained they didn’t support the Left Bloc resolution, because it left open the possibility of alliances with the misnamed centre-left parties Democratic Labour Party (PDT) and Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB), who they said PSOL should also not ally with.

A Fight Over the Apparatus

The final session of convention proved the most controversial, as debates over division of key positions within the party apparatus spilled over into physical confrontation and violence.

The convention elects an executive board to run the party for three years, but within that there are three key positions: President, Treasurer, and head of the party’s publishing and educational foundation. According to PSOL’s founding statutes, the first two positions are elected by proportional representation, with President going to the biggest tendency and Treasurer going to the second-biggest, while the chair of the foundation is appointed by the President. Because only two roles are elected, the threshold for getting at least one of the two roles is winning a third of the votes. This means that so long as the minority have one-third of the delegates, they would take the Treasurer role, while the majority take the Presidency.

In PSOL’s 3rd National Congress in 2011, which was very divided, they feared this system would make the functioning of the party very difficult. Instead, a new system was agreed which has been used for the past five conventions which sees the chair of the foundation also elected at convention, going to the third-biggest tendency. That means a simple majority is enough to win both party roles, and the foundation role then goes to the minority so long as they have over one-quarter of the vote.

This year, the Left Bloc was diminished, leaving PTL with around two-thirds of the delegates. In the final run-up to the convention, a proposal emerged to revert to the original process, which could have allowed PSOL Popular to take the two party roles and Semente to get the foundation role, leaving the minority with none of the positions.

This unleashed a major struggle inside PSOL. MES called it a “coup” and warned it could split the organisation. There were allegations that a supporter of the majority offered jobs or other benefits to delegates of the Left Bloc to get them to leave the convention without voting, and counter-allegations that the Left Bloc were trying to get Semente delegates to break with the democratic centralism of their groups and abstain. In the end, it seems that three Left Bloc delegates did leave and two from Insurgência (part of Semente in PTL) said they would abstain, ending the two-thirds majority, unless the proposal was dropped. This led to a last-minute amendment to follow the same compromise as before, with PSOL Popular winning the two party positions, and a majority on the board and MES taking the foundation role.

Convention Heightens Tensions

This outcome, however, was extremely contentious and sparked a physical confrontation near the end of the convention. Rival groups squared up to each other at the stage. There are allegations of pushing, and I personally saw a punch being thrown, all of which is now being investigated by the party. This investigation will likely be an ongoing flashpoint in the party, with rows about it already spilling over to social media.

Further conflicts and debates in the party are likely, too, particularly over relations with the Lula government and alliances with anti-Bolsonaro parts of the right in next year’s elections. For instance, the Left Bloc are warning that the new majority for PSOL Popular will bring the party closer and closer to the government, or even lead to PSOL failing to oppose anti-worker measures from the government, especially because PSOL Popular are no longer reliant on Semente. They warn that if this happens they will vocally oppose it, setting the scene for further public debates in the future.

Far from resolving the conflicts, it seems the convention has heightened them, and the waters ahead are more treacherous than ever.

Five Reflections from the Outside

PSOL has managed to build a very significant party that is known in every town and city, and within which there is a high level of discussion of ecosocialist ideas. They have rejected the isolation and insular approach of many socialist groups, and built something which has huge potential, at a scale beyond anything I have experienced.

In many ways, the debates at the PSOL convention were more politicised than those I’ve observed in People Before Profit in Ireland or DSA in the US, with various tendencies outlining developed political theses and analysis for convention. However, the main thrust of the actual debates seemed more theatrical than theoretical. It’s not just the culture of competitive chanting, but the debates themselves tended to see a lot of harsh characterisations of opponents - for instance, as coup-plotters, or as abstract academics unconcerned about poor people - rather than real comradely debate.

The venue, decorations, booklets, and general professional set-up were very impressive. However, the big budget of PSOL seems to be reliant on massive state money for political parties, with very little independent fundraising. While some tendencies adopt a policy where elected public representatives only take a worker’s wage, PSOL itself has no such position. This adds to tensions, especially given the low wages and insecurity Brazilian workers face. Jobs and money therefore became both weapons and battlegrounds in the debates. The manoeuvring over control of the foundation was an alarming example of this, and I would be concerned that a “winner-takes-all” approach in the future would lead to a split.

While PSOL has officially agreed to remain independent of the Lula government, precisely what that means is very unclear. At a session for international visitors hosted by Minister Guajajara, I asked about the tensions she felt being a minister while PSOL as a party were not in government. She replied that “PSOL are in government because I am there,” something that at least the Semente wing of PTL refutes. In reality, it seems an awkward compromise has been adopted, within which PSOL are moving inch-by-inch into a class-collaboration coalition. There is a real danger of the party being tied up in knots if controversial government policies or issues emerge, allowing Brazil’s right-wing forces a clear field to capitalise on anger if Lula’s government fails to deliver on the hopes of its mass base (as seems very likely).

Sometimes leftists internationally can cry wolf with warnings of an impending fascist threat. However, the threat of dictatorship, while set back for the moment, is very much real in Brazil. The strength of the far right, including their militias and military supporters, is beyond any comparisons with the US or EU. Military coup is a definite possibility in the decade ahead, and fighting that threat is crucial. This means united-front work, and within those united fronts ensuring there is a militant socialist alternative to the government to be a pole of attraction as capitalism’s crises deepen. There is an inevitable contradiction between Lula’s coalition - which encompasses right-wing politicians, big businesses, and capitalism - and the desires of workers, women, indigenous, and young people for a decent quality of life. The clash between those opposing forces could fuel further crises and lead to shifts right or left in the years ahead.

Article by Rupture Magazine Editor Cian Prendiville

Subscribe or purchase previous issues here.